Programming Practice: Building a deck of playing cards in Ruby 🃏

Inspired by Matthew Jones series I thought it would be fun to try modelling a simple deck of playing cards, just for fun and of course practice. Matthew mentions in one of his articles:

[…] the difficulty in creating complex software programs is not writing the code, but in getting the correct requirements.

In my experience as a writer of code and a manager of people who write code, I have witnessed this to be entirely accurate. For software developers, writing code is comfortable and poorly defined requirements are not. You can’t build what you don’t understand so we have meetings with other humans to try and gain some more understanding, to reduce the unknowns.

The point of this exercise is to reduce the unknowns by modelling a well defined domain, a standard 52-card deck (with 2 jokers, so 54 cards technically). I’m starting these exercises with a deck of cards because I hope to try building some card games in the future and being able to reference this session will be helpful.

Bedsides modelling the cards themselves, we’ll also look at an interface to the deck so we can perform various real-world interactions you might expect such as: shuffling , drawing cards and cutting the deck. I’ll be using Ruby for this, it’s the language I’m most familiar with right now so I can focus on the problem of modelling and not the language features.

Just want to review the code? It’s over on GitHub.

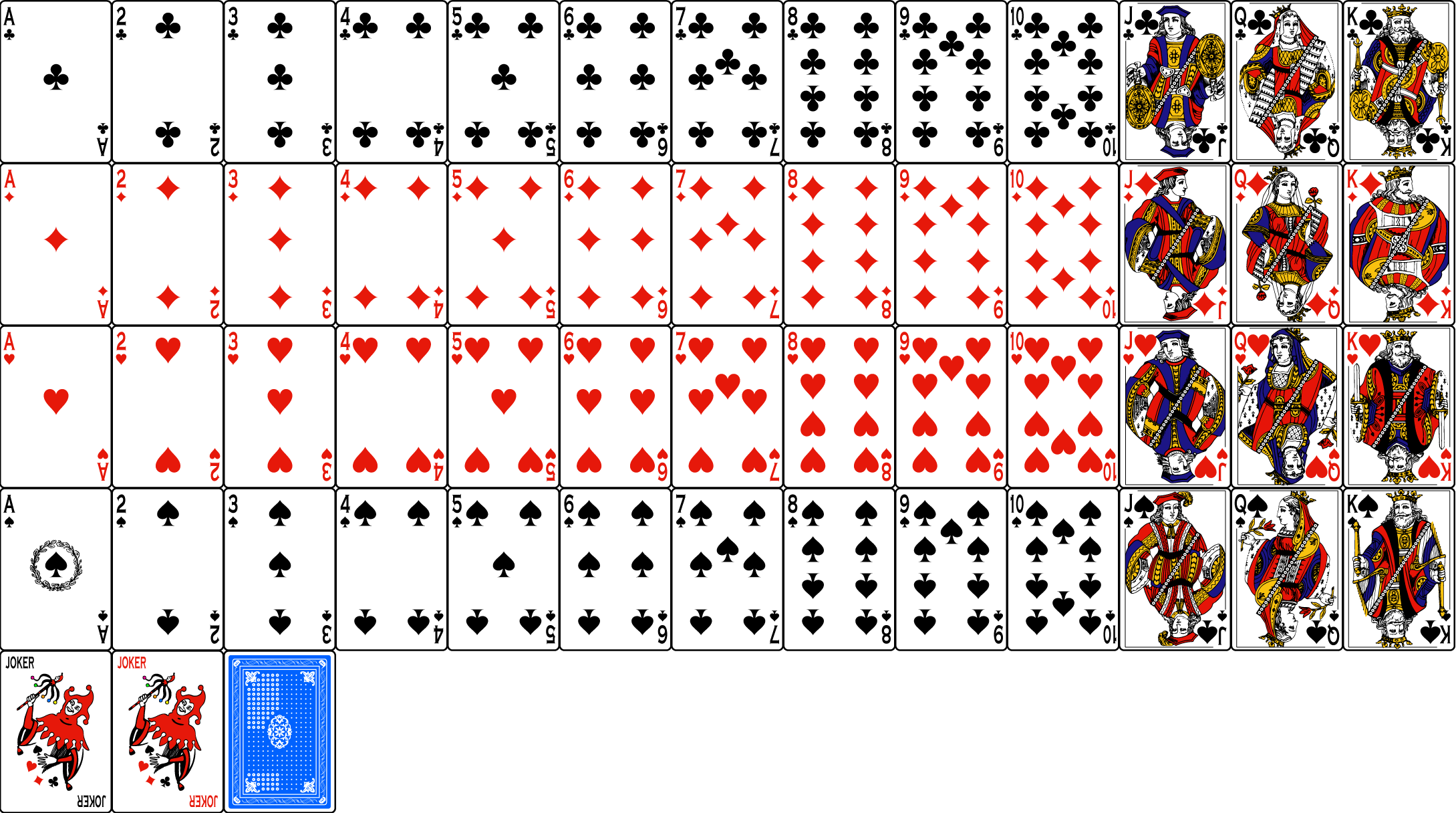

The standard 52-card deck

What makes up your standard 52-card deck? In case you aren’t familiar there are 4 Suites : Spades ♠, Clubs ♣, Hearts ♥ and Diamonds ♦. Each Suite has the same set of 13 Ranks : Ace, 2 through 10, Jack, Queen and King.

Then of course we have 2 Jokers , these are wild cards not used in all card games but are often included in a pack of cards.

Writing the first test

For this exercise I’m going to try take a strict test driven approach, that means I will work out the test first before writing any other code. I’ll be using MiniTest as my testing library.

If I had a real deck of cards in my hand right now and I wanted to check if it was a full deck quickly, I might just count how many cards there were. We can use this idea to write our first test:

require "minitest/autorun"

class CardDeckTest < MiniTest::Test

EXPECTED_NUMBER_OF_CARDS = 54

def test_deck_has_correct_number_of_cards

card_deck = CardDeck.new

assert_equal EXPECTED_NUMBER_OF_CARDS, @card_deck.size

end

end

This is a very basic test but that’s what we want right now as we don’t even know if our test works yet. Let’s write this CardDeck class exist and satisfy the test:

class CardDeck

def size

54

end

end

This is the minimum implementation required to pass our test but I’m not confident we have a deck of cards here just yet! While we don’t have a deck of cards yet the test does serve to tell us our test suite is working.

A full deck of cards

We need another test, one that allows us to check if every card in a standard deck exists, not just the total number.

Again I encourage thinking about how we might do this in the real-world? With a real deck of cards in hand, you might iterate through the deck, look at each card and check each one off against a known list of cards. To do this in our code we’ll need a couple of things:

- A trusted list of cards we expect to find in the deck.

- A way to iterate through the cards in our deck.

- Protection against tampering with the deck. For example: in the real-world, we wouldn’t want to drop any cards as we went through the deck so we need to protect against mutations to our deck

- Some way to represent the cards that make up the deck.

Starting at the top, we need a list we can trust and a method for iterating the deck.In Ruby, this is commonly represented as an #each method so we’ll keep that convention.

class CardDeckTest < MiniTest::Test

# [...]

EXPECTED_CARDS_IN_SUITE = %w(A 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 J Q K).freeze

EXPECTED_CARDS = {

"♠︎" => EXPECTED_CARDS_IN_SUITE,

"♣︎" => EXPECTED_CARDS_IN_SUITE,

"♥︎" => EXPECTED_CARDS_IN_SUITE,

"♦︎" => EXPECTED_CARDS_IN_SUITE,

"*" => %w(Joker Joker).freeze,

}.freeze

def test_it_contins_a_full_deck_of_cards

card_deck = CardDeck.new

actual_cards = Hash.new { |hsh, key| hsh[key] = [] }

card_deck.each do |card|

actual_cards[card.suite] << card.rank

end

assert_equal EXPECTED_CARDS, actual_cards

end

end

The expectations are “hard-coded” and the collections frozen. For me this helps make the tests clearer to reason about as I don’t need to run some Ruby code in my head to work out what is being created. It also reduces the risk of human error through errors in any generating code we might have written. Freezing the collection prevents modifications (as much as is possible in Ruby anyway).

A priority of any test is be clear and easy to reason about.

We have a failing test again 🥳 and a plan for the public interfaces we need to build:

class CardDeck

def initialize

@cards = [].tap do |cards|

%w(♠︎ ♣︎ ♥︎ ♦︎).each do |suite|

%w(A 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 J Q K).each do |rank|

cards << Card.new(suite, rank)

end

end

2.times { cards << Card.new("*", "Joker") }

end

end

def each(&block)

@cards.each(&block)

end

def size

@cards.size

end

end

class Card

attr_reader :suite, :rank

def initialize(suite, rank)

@suite = suite

@rank = rank

end

end

You’ll notice I also updated the #size method to check against the @cards array we built. A Card class was also introduce to hold and expose the #suite and #rank.

The Card class does not have any “setter” methods and our #each iterator does not support changes to the @cards array so I’m confident that this is not exposing obvious means to tamper with the cards via the public interface. This satisfies point 3 from the list above.

Interacting with a deck of cards

Now there is a deck of cards “in our hand” but it’s not very useful in it’s current form. We should create an interface for some of the common actions you would perform on a deck of cards so we can support using the deck in a game.

Shuffling

It would be a pretty predictable game of cards if the deck could not be shuffled. The Fisher–Yates shuffle is an optimal shuffling algorithm. Not only is it unbiased, but it runs in linear time and uses constant space. The algorithm is easy to implement however, Ruby already provides it for us through Array#shuffle. To test our shuffle we can compare:

- two unshuffled decks are the same.

- an unshuffled deck and a shuffled one are different.

- two shuffled decks are not the same.

class CardDeckTest < MiniTest::Test

# [...]

def test_the_deck_is_shuffled

unshuffled_deck_1 = CardDeck.new

unshuffled_deck_2 = CardDeck.new

assert_equal unshuffled_deck_1, unshuffled_deck_2

shuffled_deck_1 = CardDeck.new.shuffle!

refute_equal unshuffled_deck_1, shuffled_deck_1

shuffled_deck_2 = CardDeck.new.shuffle!

refute_equal shuffled_deck_1, shuffled_deck_2

end

end

For the above test, a method of asserting equality between 2 decks is required through the #== method if we are to compare the 2 decks. While the introduction of this method to the public interface is a convenience for testing only at this time, I felt it was acceptable. The cards array is shuffled in place and will mutate the @cards array, indicated by the use of bang! variation of the #shuffle method.

class CardDeck

# [...]

def shuffle!

@cards.shuffle!

end

def ==(other_deck)

cards_from_other_deck = []

other_deck.each do |card|

cards_from_other_deck << card

end

@cards == cards_from_other_deck

end

end

class Card

# [...]

def ==(other)

suite == other.suite && rank == other.rank

end

end

Our comparison method collects all the cards from the other deck into an array and then we allow the Array#== to effeciently compare each item of the arrays in turn.

Drawing cards from the deck

During a game of cards it’s likely players will need to be dealt cards or draw them from the deck. To do this, we’ll want to remove the card from the collection and return it via the method. Since we don’t have sides to our cards we’ll just assume we want to take the card off the top of the deck.

class CardDeckTest < MiniTest::Test

# [...]

def test_a_card_can_be_drawn_from_the_deck

card_deck = CardDeck.new.shuffle!

drawn_card = card_deck.draw!

deck_size_after_draw = card_deck.size

assert_equal (EXPECTED_NUMBER_OF_CARDS - 1), deck_size_after_draw

card_deck.each do |card|

refute_equal card, drawn_card, "Drawn card found in remaining deck"

end

end

end

In this test we expect the size of our deck to be reduced by 1 and for the drawn card to be absent from the deck.

class CardDeck

# [...]

def shuffle!

@cards.shuffle!

self

end

def draw!

@cards.shift

end

end

A slight change was needed to the #shuffle! method, it was returning the @cards array and not the CardDeck instance we wanted. The Array#shift method we use in #draw! removes the first card from our array and returns it. Easy.

Cutting the deck

Finally, we might also want to “cut the deck”, this means to split the deck (roughly) in half typically. From there, each half can be cut further if needed. The deck may not be cut exactly in half so we’ll need to allow for a way to specify where the deck is cut.

class CardDeckTest < MiniTest::Test

# [...]

def test_deck_can_be_cut

card_deck = CardDeck.new

number_of_cards = 10

size_of_right_cut = (EXPECTED_NUMBER_OF_CARDS - number_of_cards)

left, right = *card_deck.cut!(number_of_cards)

assert_equal number_of_cards, left.size

assert_equal size_of_right_cut, right.size

end

end

We are expecting an array of decks to be returned and for them to be the expected size. Passing this test is going to require some changes to our initializer as we will need a new deck instance with only the cards from one side of the split.

class CardDeck

def initialize(cards = build_cards)

@cards = cards

end

# [...]

def cut!(num_of_cards)

[

CardDeck.new(@cards[0, num_of_cards]),

CardDeck.new(@cards[num_of_cards, @cards.size])

]

end

private

def build_cards

[].tap do |cards|

%w(♠︎ ♣︎ ♥︎ ♦︎).each do |suite|

%w(A 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 J Q K).each do |rank|

cards << Card.new(suite, rank)

end

end

2.times { cards << Card.new("*", "Joker") }

end

end

end

After being cut, the deck is likely to be put together again so we should have a way to do that so we can control that interface. Doing this will also allow us to check if we get the same deck back after a cut.

class CardDeckTest < MiniTest::Test

# [...]

def test_a_cut_deck_can_be_rejoined

card_deck = CardDeck.new

number_of_cards = 10

left, right = *card_deck.cut!(number_of_cards)

assert_equal card_deck, (left + right)

end

end

The passing code for our test is as follows:

class CardDeck

# [...]

def +(other_deck)

cards_from_other = []

other_deck.each do |card|

cards_from_other << card

end

CardDeck.new(@cards + cards_from_other)

end

# [...]

end

With the ability to instantiate CardDeck from an array of cards it is trivial to collect all the cards together and return a new CardDeck instance.

Of course this being Ruby we have no idea that the array we’ve provided to a CardDeck actually contains Card at all, if that’s a concern then a strongly typed language would provide some confidence there.

Now I am familiar with the problem I could use it to try out a new language to get familiar with a new syntax and features without also having to think about the problem I am trying to solve.

As mentioned at the start of the article, full code is available over on GitHub.